Have Catastrophe Models Reached a Point of Overengineering?

I thought of this philosophical and potentially controversial question after recent releases of updated wildfire models by two catastrophe model vendors. The vendors added numerous attributes to their models to address recent California legislation that requires credits for wildfire mitigation measures. In one model, the number of wildfire secondary risk characteristics increased from 6 to 15, including modifiers for gutter presence, roof overhang, roof vent size and skylights. How many of these have these truly have an impact against a raging wildfire and can we really be confident in the benefit or penalty the model assigns these variables by themselves and in combination? My view is that some catastrophe models have become overly sophisticated to the point that adding more complexity actually risks decreasing their accuracy because they become excessively arduous to manage and greatly enhance risk of human error.

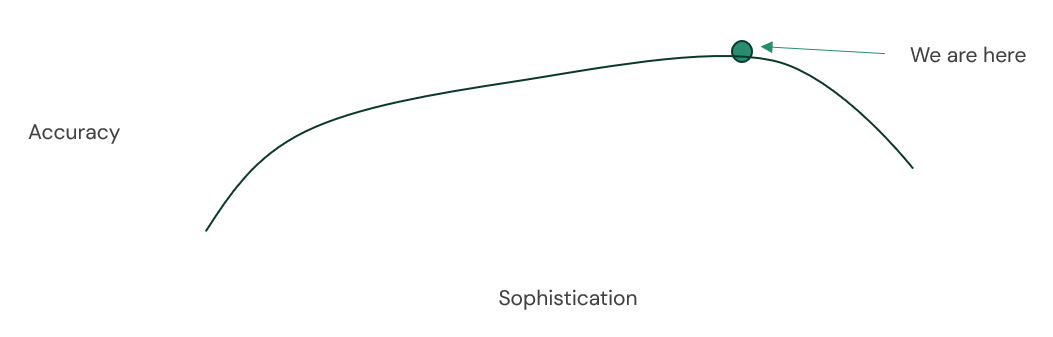

I would argue that models follow the below function of accuracy versus sophistication. The first few thoughtful advances in sophistication lead to tremendous increases in accuracy. There is then a long runway where appropriately added sophistication increases accuracy but at diminishing returns. Finally, there comes a point where added sophistication diminishes accuracy because the model becomes overly cumbersome to understand and utilize to the point of serving no purpose or worse, offering a false sense of confidence. There have been great advances in catastrophe modeling; however, my fear is that we are embarking extremely close to the downslope of that curve.

Why I believe we are at the apex of this curve:

1. There are an overwhelming number of vulnerability and financial term options within the models

2. There are too many choices for model settings (demand surge, disaggregation, etc.)

3. Excessive model optimization creates unintended blind spots

There are an overwhelming number of Vulnerability & Financial Term Options

The number of vulnerability options within the models is excessive. In addition to what we call the primary modifiers (occupancy type, construction, square footage, number of stories and year built), there are 21 secondary risk characteristics with over 130 options just for North Atlantic Hurricane in one model vendor. Beyond needing knowledge of these fields, all these options make it harder to manage interactions of the risk characteristics and generating an appropriate vulnerability damage curve. Further, there is a greater risk of having two incompatible modifiers together such as a concrete roof deck on a gable roof shape. I grant that very few or no one uses all 21 secondary modifiers, but is there that much benefit of having 21 secondary modifiers versus a smaller number?

While a book with standard homeowner risks is usually straightforward to model, more complex books with challenging financial terms can be very difficult to represent in catastrophe models. Complex portfolios can have accounts with unique risk characteristics, different location deductibles depending on peril and location, policy deductibles (12 options in one vendor), sub-limits, participation amounts, attachment points, facultative reinsurance, so on and so forth. Accurately coding these variables requires a deep intimate knowledge of a model to best represent the exposure. Incorrectly entering any of these variables can lead to severe underestimation or overestimation of estimated losses, regardless of whether the model is acceptable for the desired peril or region.

Like clutter in your home, it can be very tough to get rid of a modeling field or feature after it has been introduced. With every new model released, it seems that more features are added. Rarely are features or coding options removed. I am not arguing that additions aren’t necessary at times, but I feel it is time for a spring cleaning. Decluttering the model to retain the variables that truly matter would make the models more user friendly without sacrificing accuracy.

There are Too Many Options for Model Settings

The following are the options available when setting off a hurricane analysis in one model: model version, analysis mode, event rates, loss amplification, storm surge, vulnerability sensitivity, assume unknown for certain risk characteristics, non-modeled factors and scaling exposure values. It requires a lot of experience to truly grasp all these settings. Moreover, this level of flexibility increases the chances of analyzing a book without the intended settings. Careful understanding of an analysis profile must be taken before running an analysis.

Certainly, some of these settings, like loss amplification and storm surge, add meaningful value. But for others, how much of this flexibility is more to satisfy a perceived benefit versus just realizing it is well within the bounds of uncertainty that already exist within the models? For example, what is the benefit of having 35 different event rate sets when analyzing hurricane like there is in one model vendor?

Excessive Optimization Creates Blind Spots

If a specific type of risk in a confined geographic region exhibits very favorable modeled loss results, there comes a point where the risk of ruin becomes too large if the model is wrong or there is a punitive update to the model. For instance, concrete condos in the coastal Carolinas built between 1995 and 2010 that are 4 to 7 stories with generally protected ground-level equipment may model extremely well in one vendor, but portfolio managers would be wise to not have them comprise an outsized portion of the portfolio based solely on this modeled output. Carriers or MGAs that heavily depend on models in upfront risk selection are especially prone to overreliance, since the perceived favorable results will lead to more competitive pricing and a larger exposure concentration.

How can you adapt?

- Understand the variables you are putting into the model. Recognize and focus on the ones that have the biggest impact, like exact location, year built, construction and roof age/condition. More data into the model doesn’t automatically mean more accurate results. Understand the impact of individual variables and in combination. If the output doesn’t seem reasonable, you are not required to use an option or an entire modifier simply because you have it.

- Have consistent model settings that define your view of risk. Other scenarios may be worthwhile, but the scope of usage should be well outlined with a tangible benefit.

- Good portfolio management and sensibility matter. Visuals and deterministic scenarios can provide a commonsense check against modeled losses.

- Having a perspective from a different model(s) can identify potential blind spots. Perhaps this encourages you to reduce exposure in a specific geographic region and/or risk profile. At the very least, it can make you aware of the differences between models.

In my opinion, model vendors need to be very cautious on balancing added sophistication with ease of use and added benefit to avoid overengineering. We should not assume that increased complexity means increased exactness. Even with all the current options, the models still can’t handle items such as actual cash value policies. Moreover, any thoughtful vulnerability adjustments currently require less than ideal approaches like coding a non-applicable modifier to approximate an adjusted vulnerability curve. Would we be better served with less options but the ability to easily modify the damage curves versus trying to accommodate all the minutia of risk characteristics and financial terms? Time will ultimately tell the level of sophistication and accuracy of the catastrophe models. In the meantime, I would encourage our industry to be thoughtful with our demands of the model vendors, because more doesn’t automatically mean better.

Want to learn more about our approach to catastrophe analytics?

Contact Information

Adam Miron

Head of Catastrophe Analytics, Juniper Re

763.350.8292

JUNIPER RE PRESS

Amy Money, Head of Marketing

Juniper Re

214.533.3837